Desire to Feel Nothing

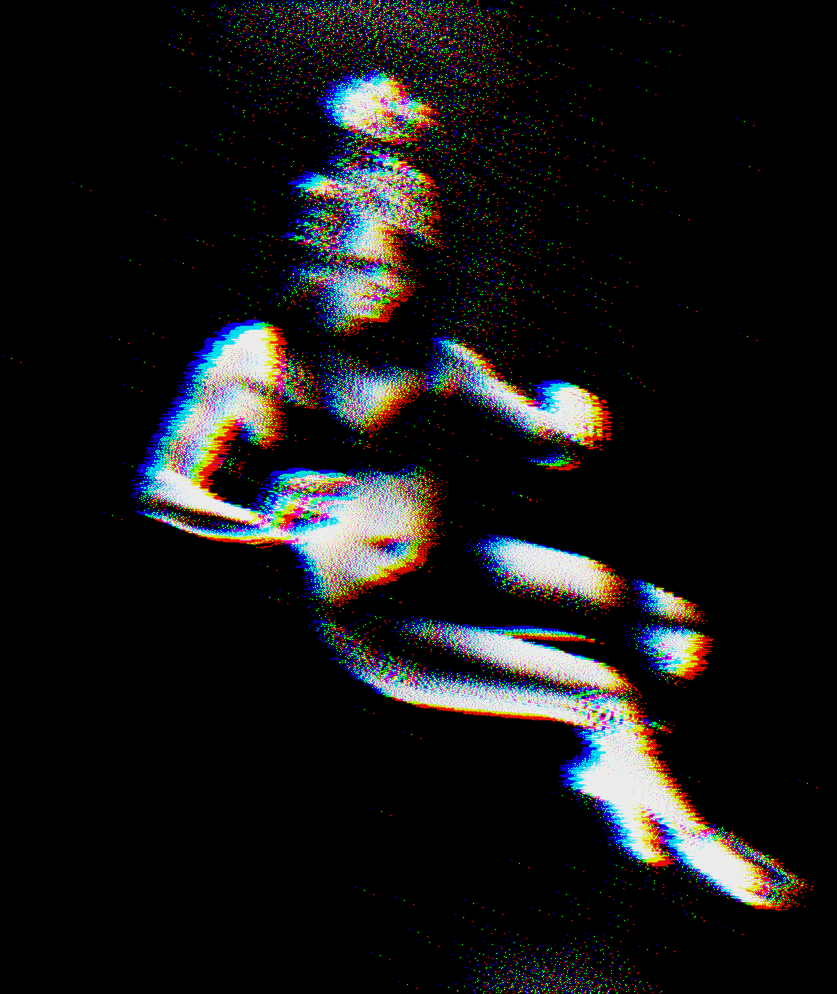

Slick with sticky salt water, I’m floating. I’m floating in a blank space and then music begins to play.

Thick, piping synthesizers rising from silence over distant waves. I’m starting to have thoughts. I’m starting to have thoughts, again. I’m Lianne, floating. Emerging from the past. I’ve no will to move and in this the heavy water supports me.

And after a time the music is joined by lights. Red, green, and pink fading in; painting the water, painting my skin. And when they’re bright enough to indicate I should get out, I drop my heels and reach for the wall. Then the smooth synthetic handle. There it is. I cleave the pod like a car boot or perfectly sliced egg, then step onto the tiled floor. Leaving the whirring apparatus behind. There’s clothes and a branded towel on the bench. Every item feels distinct. Not mine, like they’re plucked from behind a stage curtain. But even in the daze of emergence, I know I have to use the showerhead in the corner to slough the salts from my body before I can use the towel. Before I pull the clothes over my head to become myself again.

–

The logo’s on the pod. The logo’s on the towel. Infinity, the sideways 8, beneath the power symbol – the circle bisected at its apex by a brief straight line, which are in fact a one and zero. Binary. Something, nothing, infinity. I realise I lost more than stress and muscle tension in the pod. My hold on time is fizzy, and I feel lighter than I should. I’m looking back over my shoulder at the open pod, lit now in a pink and periwinkle glow. Sad to depart from such a beautiful thing. The plum surrendering its stone. The light on the water is mesmeric. But the music’s still playing, louder, really insisting now that it’s time to move on.

–

This business is small. They don’t have enough corridor to get lost in. In the cramped cooldown corner a thirtysomething shimmies past me to the only hairdryer and mirror, leaving me the wicker table and chairs. I sit. Twin pints of water stand waiting. And there’s nothing, really, in my head. I feel unfolded but new thoughts aren’t forming. My glass flies up featherweight then feels heavier once I’ve drained it. The other woman takes the opposite chair so I flee to the drier. Look into the mirror, looking for Lianne, as the drips fly from my sopping hair. There she is, waking up. Thank you, mirror.

Back in my chair, and just when I notice that the woman opposite is staring at me, pain shoots through me. It’s the kind of pain you hope will pass quickly, and it’s in my belly so I grab it. I press here and there in case there is gas I can displace, but that makes it worse.

“Everything okay?” asks the other woman, and I look up at her. I see cold eyes and pinched cheeks and complex makeup. I see black hair (not like mine – her’s is dyed, and wavy). I see a net of scars and tattoos extruding from her smart sleeves. It’s funny that she was staring at me. With me, there is far less to survey. I’m all crumpled cotton.

“I’m not sure,” I reply, which is stupid because I am sure.

“It’s your first time coming here?” This other woman, she’s sitting really straight. And her questions don’t exactly seem like questions.

“Yes…” I manage. Then amid the pain, a flit of déjà vu.

“You might be acclimatising wrong,” she says, calm to a point I dislike. “Consider. You spent an hour cooking in the pod, and you’ve just thrown a pint of fridgewater inside yourself.”

I nod, letting her scold me, which I shouldn’t. Boundaries matter. “I did,” I admit. “Stupid of me.” I lean back a little and notice there is synth music here too, piping gently. Then another gurgling bolt of pain comes and I wince.

The other woman frowns and cups her chin. “Babe. Come on. Good odds you’ll survive.”

“Please don’t call me babe.”

“I should have asked your name.”

“It’s Lianne.”

“Suits you. You’re lucky. I was christened ‘Angel’.”

“Oh, that’s…”

She sips her water. Only sips. “I’d blame my dad for it, but I try to keep him out of my head. Anyway. I go by Angelina. And never Angela. It’s all very fraught.”

“I get it. Lianne is just my English name.” The notion comes to me like a once-lost memory. “People can’t pronounce my real name so I never share it. Is that too weird?”

“Yes, it’s ludicrous. How’s the pain?”

I touch the sore spot to test it, but it’s like prodding a zit. “It’s still not great.”

“Get some air. In fact, fuck it. I’ll go with you,” says Angel, who I know I should think of as ‘Angelina’ but somehow cannot. She leads me out past the reception, where the man who should be there is not.

–

We stand with our backs to a terraced hub of office units, all cased in girders, facing a canal which we follow into a quiet area the signs call New Islington. Round two bends we reach an urban village of little balconied residences spread across the water, interlinked by black iron bridges, brick walkways and benches, and short pointy fences painted white. I’d call it heaven if not for the smell, and the deposits in the water: bikes, trolleys, traffic cones. But there are fish – scrappy schools of minors policed by their parents. I feel like I’m watching another world through crystal. I feel something like love. But really I’m sitting on a ledge in pain, with a strange Angel beside me.

“I’ll pick up soon.” I mumble. “You don’t need to stay.”

Angel flickers for a second, then says, “I don’t need to leave either.”

And I’m following the fish again. I can almost recall the species. It must be rare for so many to survive in such bad conditions. Eventually I realise I should speak, so I ask Angel how often she uses the pods.

“You get the impression I’m a regular?” she asks. I frown and nod. “Well, you’re smart.”

Sadness washes over me, though I don’t know why. Maybe it’s knowing the woman beside me bears so many scars. Maybe it’s the sight of the little fish drifting between bicycle spokes. “Why do you come?” I ask, and she starts staring daggers at the ground.

“It’s a long story. One that will affect you.” She pauses. “I’ll leave if you don’t want that.”

I turn my face to the sky, which looks better than it should. Deep matte blue. And the clouds are the shape I like best. Maybe after my hour in the dark I’ve returned with kinder eyes.

“I’m serious,” Angel says. “I can bounce, right now.”

“No, stay. I want to hear your story.”

She nods. “Alright.” Her fingers are clutching the lip of our little ledge. This close, I can see her tension written on her. Painted thorns and lingering scratches. People are covered in clues, but without a cipher they’re easy to misread. An Angel speaks…

–

During my childhood, I felt like there was a rulebook for life, and my copy had been confiscated. I didn’t understand how to join in games. I didn’t know how to ask for the bathroom. Timings, wordings, poses, postures. I didn’t know any of that. Nobody told me. In the end I learned how to pretend. In lieu of a shortcut to understanding everything, pretending would suffice.

At home we never had one day consistent with the next, and it was pointless asking questions. Past a certain age visitors told me, as if trained, that I had my mother’s mind and my father’s genes. They also spoke about his willpower. He hit me for the smallest thing. He’d invent new ways to do it. I didn’t know why. Mum wouldn’t stop him. People told me he’d seen most of the world before I was born. People told me he was a genius, capable of anything. And yet I was told we were too poor for holidays or birthdays.

It’s true he was good with his words. They were like snares buried inside of mum. And his stare. When he fixed it on you, you wanted to run but couldn’t. When he left, he shredded us on the way out. When mum lifted anchor people stopped saying I had her mind; by that point it was insensitive.

But until he left it was never dull. It was all his show. He’d bring in new people every week and transform them. He’d close off half the house. Mum would vanish into her room for days at a time. But somehow he was hilarious. No straight answers, only games.

Is mummy having one of her funny spells? Is daddy playing one of his tricks?

I think everyone eventually has to balance what ‘normal’ means inside and outside the family home. I… really struggled with that. And with when to leave. First I grew sick of caring for mum, then it was the entire shithole town. I wanted a passport. To be a rover like my dad. I’d imagine myself studying under him, the genius, even if it meant being spanked again. At least that would be attention.

But one phonecall killed that fantasy. It was a Thursday, and I was by the living room window. I recall hail striking the glass, then mum passing the handset. Calls were products of his whims, twice or thrice yearly, never with news. On that dreary day I was old enough, sad enough, desperate enough, to try and use the call for myself. I asked him to come back and rescue me.

“Did it work?”

Of course not. Dad never played his ‘yes’ or ‘no’ cards. To use a phrase he loved, ‘there are so many ways of speaking’. Which is true. It becomes scary to contemplate. Anyway. My asking spiralled to begging. He’d won. Pushed me into screaming down the line. ‘I can’t do this.’ ‘I don’t want to be me anymore.’ ‘I wish I was someone from far away – anywhere, the moon!’. And that did something. ‘You really want that?’ he said, very quietly.

We had this moment of silence and he slowed right down. I think I really had – if only for a moment – dammed his flow. When he spoke next he seemed to be choosing every word very carefully. He said that granting that wish would mean nonexistence. Not to see my name crossed out of the celestial registry, but for it to have never been etched there in the first place.

I swallowed and I said that would be fine. Nonexistence. It sounds fine. I still believe so. But the next sound that came out of the phone… it didn’t sound human. I recall the words ‘washed away’, and he kept calling me small. Tiny, mini, little. Like he was firing a shrink ray at me. And my last memory of that entire day is the disconnect tone.

“How old were you?”

Twelve.

“So you grew up fast. You had to.”

Yes… I tried. Not far into secondary school I was considering how to obliterate myself without dying. Would you call that grown up too?

“I…”

Pushing to extremes is interesting. It brings in a sort of pride, and there’s always someone to cheer you on. And a false idea that you can get a thing ‘out of your system’ by doing it to death. But of course there is no ‘system’, and exploring desires only carves them into you. Riding the helter skelter down into hell.

“…what were you doing?”

I tried everything, eventually. Desire is a bottomless hole. Sex was my first resort. I started way too young. Actually, you don’t want to know. You’re sweet. You don’t deserve this bucket over your head.

Over a course of… years… parts of me left and didn’t come back. That’s all I’m telling.

“I’m sorry.”

Be sorry, be jealous, it doesn’t matter.

Next it was painting. Painting utter shit, but it led me to the edge of an exit. Only the moving hand and frozen eye left lingering in this world. And my family name drew in the ‘scene’. For fifteen minutes I was in. By the sixteenth, the self-identified ‘freaks’ had no room for me. Stupidly I’d thought unorthodoxy was the point. And I’d nearly lost sight of why I’d started. The vanishing. A road to leaving this world without leaving.

And given that I was not merely playing at precarity like my freshly-scarce friends, I needed to work.

Forget art. The office is the real domain of the freaks. And they nearly had me. Lumbering up the ladder where warmth can’t follow. A rancid crust building around my organs. I felt that I was learning how my father operated. Using words as the engine to one’s will. One thousand tiny games…

We think work is the most normal thing of all. No it’s not. That’s the trick it plays. One day in the communal kitchen I blinked and the lark fell away. I remembered what I wanted and could not go back to the computers and emails. And the useless people. All these attachments I’d built up were a spider web. Easily destroyed.

So I began starving myself. If you can’t sever stimulus, deny fuel. Boil down to the core system. No use of course. Hunger is pain. Pain is a stimulus. It’s the intrusion of reality on the body. Never starve yourself.

Next, something basic. Drugs and alcohol. No use. Reality comes back worse every time. Then it was sex again; I never said I was clever. Long nights sliding into the skin of an animal, thinking maybe I’d missed something on my first spin around the pole. Disgusting.

So, a final angle. Time for something wholesome. Vitamins and minerals. Friendship. An open heart. Finding meaning in simplicity and goodness.

I wish I could say it worked. One year of trusting in common sense and the love within others combined every problem I’d faced before. Lust, vanity, dependence, compromise, plus… an awakening to the horrid omnipresence of puppetry. Instrumentality; one player using another. Once you begin to notice it everywhere, all around you, you’re poisoned, and you realise that intelligence is the poison, and we’re ruled by it. So Lianne, just know, I’m not trying to use you for that today, I promise it’s not personal –”

–

…and I grip Angel’s arm, just tight enough to halt her words.

“You’re being unfair to yourself.” I’m shocked at my own stridency.

Angel’s eyes fall on my hand. “Pardon you. I haven’t finished.”

But I’m not dropping it. It’s my turn to be juvenile. “You were hurt in your childhood, but that doesn’t mean you should drive yourself mad hunting for a magic cure.”

“Lianne…” she says softly. “Let me go.”

And I comply. I just fold. It’s embarrassing.

“How’s your stomach?” she asks.

“…almost back to normal.” Half true. The world seems sharper, like I’ve put on new glasses. Is it a delayed benefit from the pod? Or is it because I’ve been listening so closely to my new friend?

Angel stands. “It’s cold. Look. I know a good café nearby. Tag along?”

I nod and follow because she’s already walking. Angel, I know, is probably still unwell. But it doesn’t feel like she’s going to push me into the canal. It’s low odds, anyway.

“I just realised – I still haven’t told you why I use the float centre,” she notes, turning back to me.

I had forgotten I asked. I’m glad Angel reminded me.

–

It’s a dim venue. Moody. We’re left alone in a shadowy corner, leaning to hear each other over pulsing, receding music. Angel fills my view; frosted glass in hand. I’m listening to her. I should be tougher. I should. She’s so presumptuous. But she’s talking, and I’m listening. And it’s strange how easily her words become my visions.

–

So you had it right. I wanted a magical cure with no side effects. And it was dead end after dead end. But if you knew you had even a slim sliver of a chance to end all pain, why would you ever stop? You might never know how close you got before walking away. And the longer you hunt, the wiser you get.

So by the time I first heard of sensory deprivation – and that it was something you could rent immediately rather than work toward over decades – I understood that it was what I wanted. Not existential struggle. Not death by kamikaze. Quietude. Nothing to remind the mind it is alive.

In theory.

In practice, there’s still the water.

And all your aches. And your arms. Your legs. Hair and genitals and eyeballs – especially if the salt gets in them. And the pods themselves… you’ll have noticed how easy it is to brush against the side. Drift once and it’s a sure thing.

So you can get close to gone. Close to escaping your own stupid swirling ideas. And then, one little tap reminding you that you’re chained to your body and trapped on the planet.

And yet. I was old enough to accept ‘good enough’. With practice, my mind was staying quiet long after I left the pod. And with no pain or poison. Just travel, and the one-hour fee. I didn’t get addicted, or do it to death. Eventually I felt ready to let it go. Like I was casting off the wounded little child inside of me. Bon voyage, little one.

But one day, on what might well have been my final visit to the float centre, I left my pod to find a man in the cooldown corner, standing and staring at me. Me with my wet hair. Me, dazed, and calm, facing his piercing stare. He had all-white hair, long enough to tie back. Weathered but healthy, hands clasped behind his back, shirt smart but not tucked in. Suddenly it clicked, like I’d been burying the answer, and like an idiot I just said it: “Dad.”

He spoke softer than in my memories, and less. He still smiled like the devil might. Still wouldn’t hug me. He asked kind questions, he made loving promises… Days after, I realised they had all been chess moves.

He can steer you. He does it very easily. He had me crying with snot trickling out my nose. And the eyes – I’d forgotten how he fixes them on you. I told him about my wish to become nothing. And he asked if the pods were working for me, and at my first caveat he’d pulled out a little brown card. Nigel and Sonia, Tunnel House. They have something better, he said. The address read ‘Cleft’ – suburbs clustered on a distant market town, long past use. Go down into their tank you’ll never hit the edge, he promised. I don’t remember how we concluded, but I remember turning back to find him gone. I tried every door. But he had vanished, and there were no staff present to question.

I had a shower thought the next day: that my dad owned the float centre, and had used a keycard to retreat somewhere unseen. I found the notion horrid and wrote it off as something I’d dreamed rather than a possibility, which – unavoidably – it is.

–

I’ve closed my eyes now. I’m deep inside Angel’s story. This room is very dark and it’s a cosy little corner we’re nestled in. Her face and hands are all I really see when I peek through my lashes.

–

I hesitated for six months. Fearing something invisible. I changed to another float centre, more expensive, far from the city centre. In town and near home I found myself glancing into second storey windows. As if there were a blade or demon dangling above me. So for better or worse I looked out the little brown card.

I struck an indirect approach to Cleft. I parked at a train station miles away then walked pavements to another on a different line. Then took a two-carriage slugger to a proximal town. Selected a bus stop on a sealed-off strip of bungalows, and from there rode to one village south of Cleft. Then I skimmed lanes and footpaths into its outskirts.

The whole place felt overgrown. Damp, and some parts only half-rebuilt as if sketched from memory. In the wealthy quarter the trees were old; tall enough to form a canopy blocking out the rain. A twisting march over strata of macadam and leaf-rot brought me to Tunnel House. On its once-lordly street, bins overflowed and the tallest homes were divided into zigzag flats. But my father’s contacts had held onto theirs, it seemed. Four storeys and a basement, all under one name and number. 88, Tunnel House. I climbed five concrete steps to rap the door. Behind the flaking paint came a flapping sound and soon a sordid man revealed himself.

“Nigel,” he said, gesturing to himself indifferently. Slippers, crusted dressing gown, ancient jeans. Long wispy leftovers for hair hung around a flaking crown. “You’re Angel, no?”

“Angelina,” I said. “And is Sonia there with you?”

“Not even slightly,” Nigel said, then beckoned as he drew back into his dim front hall. The front door jammed until I wrestled with the nib. Nigel did not step in to help. The state of his carpet persuaded me not to add my own boots beneath a crooked coat rack from which I divined that Sonia existed – or that Nigel crossdressed.

“This way,” called his voice from somewhere below. I traced it to a door more lacklustre than the last. Nigel was waiting for me behind it, down a staircase in a floorboarded play-hall. He had darts. He had pinball. And there were apparatus I recognised from childhood but could not name. These were machines I’d seen my father operating. My host was perched on the arm of a battered tuxedo sofa, arms folded.

“I had a call saying you’d come, about floating, yes?” He sounded exhausted with me. Already.

“Yes. Is there a charge?”

“Never is, not here. You’ve mistaken me for a business.”

“Happy days. Although… I don’t see where the pods could be.”

“Yes. You don’t. What else do you not see?” Nigel exhaled once through his nostrils, then loosed the solution without even letting me try. “The trapdoor. Far corner.” He pointed.

There it was, in a square outline and a varnished handle glinting under Nigel’s cheap tungsten bulbs. There was no chance I’d have noticed it if not directed, but why bother retorting? I approached the trapdoor circuitously, asserting my ability to set the pace. Self-defense.

“It’s down there,” he said, turning his head to follow me like a haunted suit of armour. “No pods, just one big pool. Salty enough that you’ll float, and huge. I can’t promise clean. I can promise reasonably clean. And I can only promise safe if you don’t lose sight of the ladder.”

“Sight? What sight?”

“I was speaking figuratively.”

“Will you open up if I shout? And how long’s the session – an hour?”

“…Yeah.”

“Yeah to what?”

“Your question.”

“Don’t be a dick.”

“…Don’t be a bitch.”

Hard to know how to deal with men like this, isn’t it? The kind who always want to escalate. I opted to spit on his grubby floor. “There were two questions.”

Nigel flashed teeth cleaner than any part of him. For a quarter-second they outshone the bulbs. “Just testing. If you want out the hole, shout. I’ll hear. Door opens, light comes in, you climb out. But I’m sure you’ll ace your spell in the deep. Dad speaks well of you. The hour, Angel, is yours.”

Now that he was orating, I picked up Nigel’s accent. Northumbrian. An old strain of it, or a mongrel blend. “That’s it?” I asked.

“That’s it. It all led to this, Angel.”

“Angelina is better.”

“I hope she is.”

“No thanks to you, and your generation.”

Rather than answer, Nigel began to pick a nail. Theatre. Perched like a ragged lord on his sofa.

I moved closer to him. “I want to ask something about my dad.” No echo.

“Let’s just do one question,” Nigel offered.

“Fine. How many children does he have?”

That made Nigel tilt his head, so that his skullet straggles dangled. “Dear miss, I’ll tell you this. Your father and I, we do everything through proxies.” He blinked. Even smiled.

I insisted. “How many do you think he has?”

“We agreed one question.”

“Come on. Don’t be a bitch.”

Nigel almost smiled. He drew up his legs to balance on the sofa arm in yogi posture. Chewing on his thumb, he answered. “It’s either dozens, or it’s just you. That’s my punt. Happy?”

“Peachy sunshine and yellow roses.”

The exhaustion returned. He rose and began a slow pace up the room. “Good. Now. You, please, go trapdoor. Open. Down. Me close trapdoor. You, float.”

“I’ll need privacy to undress.” I had taken this as a given, but could see my host was no giver. “And I’ll need to trust you not to steal my clothes.”

“Miss. I’m not a pervert. Like you, I am a renunciate. An old… psychonaut, circling lost innocence.”

I brushed off the babble. “Hm. When was your wife last down here, Nigel? ”

Nigel stopped to splay ten sunburned fingers. No ring. “Sonia is my half-cousin. A good woman, currently out shopping. And if it matters to you…” he sighed, “….she exists. It is vital to attach oneself only to things which exist.” He proceeded to a corner of the play-hall and turned to face it, like a naughty boy. And did not speak again.

“Does ‘innocence’ exist?” I called out.

But as I mentioned, he did not speak again.

So I bent and pulled the trapdoor’s half-moon handle to reveal, reaching out through blackness, the upper rungs of a dark iron ladder. Lukewarm air rose from the open pit. And this felt like an arrival. I shed my clothes hastily and descended. A square of faint light hung above me until I was very far down, near the water, and then with no sound it was shut from above.

One can only begin flotation trusting you will be undisturbed. That you will float. That your thoughts will slacken. That your muscles and gut will comply. That time will dilate. It’s a lot of faith to hand over all at once. So I took my time on the ladder’s final rungs as my toes, ankles and the rest pierced the still waters, and kept gripping until I found the bottom; something organic, not quite mud. And wading out three paces waist-deep, no sign of a wall. No way to glean the water’s colour. No wish to taste it. No smell to speak of. No telling how this place was made.

I had every reason to turn and haul myself back up and away, before I lost the ladder. But… to go back to what? I did not like the world. I still do not like the world.

I let my feet leave that curious benthic floor and rise level. Tilted back my chin so the water would hold me. All around: blackness, which sometimes in the pods you will see spinning or punctuated with colours. No scent nor skim of a barrier. I encountered a brief fear that one animal or more might be sharing the water, but soon found the idea amusing; picturing a doggy-paddling giraffe. Staring into nothing and not thinking of my father, nor craving any high, nor wishing for the company of a friend or lover, old faces came to me unbidden but I did not recognise them, and they left me.

A sense of drift arrived in time, perhaps false, perhaps a spiral, but the idea of a current pleased me more – as if this were not a pool but an underground river carrying me along its course with little to no meander between high halite walls and a curved cavern ceiling. This fantasy soothed me and I fell into a daydream where the flow brought me, after years, out to open waters, never-mapped, and then following days on tepid, aimless waves I woke to sudden friction. I rolled and ragdolled on bleached shingle, slapped by sunshine, washing up on calcium sands – a dispopulous, terminal beach where distant karsts punched into peacock blue skies. And my father was there, atop a ridiculous bamboo chair, and you were there too, Lianne, my friend from afar. You were there, sitting at ease on a mint green polka dot picnic blanket, chewing wild fruit as the surf delivered me to you. We compared our black hair, our dissimilar skin. Identical hands. But it was a dream. It was a dream. Because when you pulled me ashore I saw you looking down on me and I saw my father’s face too. His cruel, apelike face.

This visage triggered an inarguable stillness, as the atmosphere twisted from tropical to clinical, and I felt myself responding with nothing but indifference to a pair of hands, choking me, and my hands choking another. Jaws closing on my calf, and my own teeth cleaving something like half-baked dough filled with steaming juices, and in the dream I shut my eyes as impossible memories streamed in, some patently false and others hauntingly familiar.

Our tiny feet in red sandals barrelling down a corridor to chase a floating balloon. How did it know to turn the corners? Then a waterfall whose thunder I observe from a remote precipice, while also watching another me from outside myself, and I see myself vanishing into the crowds on a gleaming subway platform. And I’m lying in inch-high lawn-grass turning wild, and feel I am in another country, too old or tired to move, and it begins to rain, indefinitely, until there are ponds below and pinprick stars overhead. Someone else was exhausted. Now I am exhausted. We are floating, in a blank space, and I don’t think we have words anymore. Don’t have words anymore. Don’t have them, and hear thick synthesisers piping in a gentle sequence of cherry waves. I’m starting to have thoughts again. I’m emerging from the past. I’ve no compulsion to move and in this the water supports me. Pushes me to its surface, like my mother.

Then lights, fading in. That means it’s been an hour. All the lines painted on my body have been washed away. When I stop floating, I reach for the rocky wall and find a smooth synthetic handle. There it is. And I open the pod like a car boot smoothly sliding or a perfectly sliced egg or a plum conceding its stone. Opening to a dark tiled room with a bench facing me and a shower in the corner. And behind me, the whirring, marvelous apparatus powering the pod. There’s clothes and a towel waiting. But even in the daze of my emergence, I know I must first use the showerhead to slough all the salts off my body. Before I use the towel. Before I pull the clothes over my head to become myself again.

–

From seclusion in our cosy corner, and a life that I never understood, I awaken to a halo of glowing dark surrounding someone I have only just met and do not know, and the face I stare into is like a breaking mirror, and her hands are dust, passing away from this world.

Angus Stewart writes strange stories and essays that have found home in publications including Necksnap, Big Other, and Typebar. He hails from Dundee, lives in Stockport, and ran the Translated Chinese Fiction Podcast for five years.